Birth of Race-Based Slavery in the American Colonies

The Birth of Race-Based Slavery in the American colonies…by the 17th century, America’s slave economy had eliminated the obstacle of morality. During the second half of the 17th century, a terrible transformation, the enslavement of people solely on the basis of race, occurred in the lives of African Americans living in North America.By Peter H. Wood, excerpted from Strange New Land: Africans in Colonial America by Peter H. Wood. Published by Oxford University Press. This article supplements Episode 1 of The History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. Please join Slate’s Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion for a different kind of summer school. To learn more and to enroll, visit Slate.com/academy.

Color line drawn in American colonies in 17th century

During the second half of the 17thcentury, a terrible transformation, the enslavement of people solely on the basis of race, occurred in the lives of African Americans living in North America. These newcomers still numbered only a few thousand, but the bitter reversals they experienced—first subtle, then drastic—would shape the lives of all those who followed them, generation after generation.

Conditions worse and worse for Black people in Colonial times

Like most huge changes, the imposition of hereditary race slavery was gradual, taking hold by degrees over many decades. It proceeded slowly, in much the same way that winter follows fall. On any given day, in any given place, people can argue about local weather conditions. “Is it getting colder?” “Will it warm up again this week?” The shift may come early in some places, later in others. But eventually, it occurs all across the land. By January, people shiver and think back to September, agreeing that “it is definitely colder now.” In 1700, a 70-year-old African American could look back half a century to 1650 and shiver, knowing that conditions had definitely changed for the worse.

Some people had experienced the first cold winds of enslavement well before 1650; others would escape the chilling blast well after 1700. The timing and nature of the change varied considerably from colony to colony, and even from family to family. Gradually, the terrible transformation took on a momentum of its own, numbing and burdening everything in its path, like a disastrous winter storm.

Unlike the changing seasons, however, the encroachment of racial slavery in the colonies of North America was certainly not a natural process. It was highly unnatural—the work of powerful competitive governments and many thousands of human beings spread out across the Atlantic world. Nor was it inevitable that people’s legal status would come to depend upon their racial background and that the condition of slavery would be passed down from parent to child. Numerous factors combined to bring about this disastrous shift—human forces swirled together during the decades after 1650, to create an enormously destructive storm.

Racial stratification in Latin America too

By 1650, hereditary enslavement based upon color, not upon religion, was a bitter reality in the older Catholic colonies of the New World. In the Caribbean and Latin America, for well over a century, Spanish and Portuguese colonizers had enslaved “infidels”: first Indians and then Africans. At first, they relied for justification upon the Mediterranean tradition that persons of a different religion, or persons captured in war, could be enslaved for life. But hidden in this idea of slavery was the notion that persons who converted to Christianity should receive their freedom. Wealthy planters in the tropics, afraid that their cheap labor would be taken away from them because of this loophole, changed the reasoning behind their exploitation. Even persons who could prove that they were not captured in war and that they accepted the Catholic faith still could not change their appearance, any more than a leopard can change its spots. So by making color the key factor behind enslavement, dark-skinned people brought from Africa to work in silver mines and on sugar plantations could be exploited for life. Indeed, the servitude could be made hereditary, so enslaved people’s children automatically inherited the same unfree status.

But this cruel and self-perpetuating system had not yet taken firm hold in North America. The same anti-Catholic propaganda that had led Sir Francis Drake to liberate Negro slaves in Central America in the 1580s still prompted many colonists to believe that it was the Protestant mission to convert non-Europeans rather than enslave them.

Apart from such moral concerns, there were simple matters of cost and practicality. Workers subject to longer terms and coming from further away would require a larger initial investment. Consider a 1648 document from York County, Virginia, showing the market values for persons working for James Stone (estimated in terms of pounds of tobacco):

Francis Bomley for 6 yeares 1500

John Thackstone for 3 yeares 1300

Susan Davis for 3 yeares 1000

Emaniell a Negro man 2000

Roger Stone 3 yeares 1300

Mingo a Negro man 2000

Among all six, Susan had the lowest value. She may have been less strong in the tobacco field, and as a woman she ran a greater risk of early death because of the dangers of childbirth. Hence John and Roger, the other English servants with three-year terms, commanded a higher value. Francis, whose term was twice as long, was not worth twice as much. Life expectancy was short for everyone in early Virginia, so he might not live to complete his term. The two black workers, Emaniell and Mingo, clearly had longer terms, perhaps even for life, and they also had the highest value. If they each lived for another 20 years, they represented a bargain for Mr. Stone, but if they died young, perhaps even before they had fully learned the language, their value as workers proved far less. From Stone’s point of view they represented a risky and expensive investment at best.

The Birth of Race-Based Slavery in the American colonies

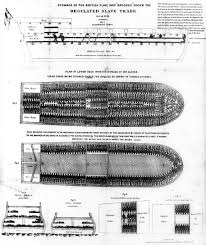

By 1650, however, conditions were already beginning to change. For one thing, both the Dutch and the English had started using enslaved Africans to produce sugar in the Caribbean and the tropics. English experiments at Barbados and Providence Island showed that Protestant investors could easily overcome their moral scruples. Large profits could be made if foreign rivals could be held in check. After agreeing to peace with Spain and giving up control of Northeast Brazil at midcentury, Dutch slave traders were actively looking for new markets. In England, after Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, he rewarded supporters by creating the Royal African Co. to enter aggressively into the slave trade. The English king also chartered a new colony in Carolina. He hoped it would be close enough to the Spanish in Florida and the Caribbean to challenge them in economic and military terms. Many of the first English settlers in Carolina after 1670 came from Barbados. They brought enslaved Africans with them. They also brought the beginnings of a legal code and a social system that accepted race slavery.

While new colonies with a greater acceptance of race slavery were being founded, the older colonies continued to grow. Early in the 17thcentury no tiny North American port could absorb several hundred workers arriving at one time on a large ship. Most Africans—such as those reaching Jamestown in 1619—arrived several dozen at a time aboard small boats and privateers from the Caribbean. Like Emaniell and Mingo on the farm of James Stone, they tended to mix with other unfree workers on small plantations. All of these servants, no matter what their origin, could hope to obtain their own land and the personal independence that goes with private property. In 1645, in Northampton County on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, Captain Philip Taylor, after complaining that “Anthony the negro” did not work hard enough for him, agreed to set aside part of the cornfield where they worked as Anthony’s plot. “I am very glad of it,” the black man told a local clerk, “now I know myne owne ground and I will worke when I please and play when I please.”

Anthony and Mary Johnson had also gained their own property in Northampton County before 1650. He had arrived in Virginia in 1621, aboard the James and was cited on early lists as “Antonio a Negro.” He was put to work on the tobacco plantation of Edward Bennett, with more than 50 other people. All except five were killed the following March, when local Indians struck back against the foreigners who were invading their land. Antonio was one of the lucky survivors. He became increasingly English in his ways, eventually gaining his freedom and moving to the Eastern Shore, where he was known as Anthony Johnson. Along the way, he married “Mary a Negro Woman,” who had arrived in 1622 aboard the Margrett and John, and they raised at least four children, gaining respect for their “hard labor and known service,” according to the court records of Northampton County…