Three Books About The New Cold War

Three books about the new Cold War… “Not since the days of Ronald Reagan has Russia played such a prominent role in US political life. After Donald Trump’s shock victory – greeted in the Russian parliament with cheers and champagne – came accusations of Russian meddling in the US electoral process…” More about this in Three Books About The New Cold War…The London Review of Books Vol. 39 No. 5 · 2 March 2017

Eat Your Spinach

byTony Wood

- Return to Cold War by Robert Legvold

- Polity, 208 pp, £14.99, February 2016, ISBN 978 1 5095 0189 2

- Should We Fear Russia? by Dmitri Trenin

- Polity, 144 pp, £9.99, November 2016, ISBN 978 1 5095 1091 7

- Who Lost Russia? How the World Entered a New Cold War by Peter Conradi

- Oneworld, 384 pp, £18.99, February, ISBN 978 1 78607 041 8

Not since the days of Ronald Reagan has Russia played such a prominent role in US political life. After Donald Trump’s shock victory – greeted in the Russian parliament with cheers and champagne – came accusations of Russian meddling in the US electoral process, followed in January by the leak of a dossier claiming that the Russian authorities had accumulated (even more) compromising information on Trump.

More recently there have been alarms over the Kremlin’s connections with and possible influence on the incoming secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, and Trump’s now ex-national security adviser, Michael Flynn. The rhetoric emanating from US politicians and media commentators too seems to be drawn from another era. In November, a murky online group called PropOrNot went full McCarthy by releasing ‘The List’, designed to name and shame – or indeed casually smear – websites which it believes ‘reliably echo Russian propaganda’.

In January, Fox News rolled back the years by announcing that there was ‘no Soviet source’ for the DNC leaks, and the title of a piece in the New York Review of Books – though it was soon corrected to reflect events since 1991 – asked: ‘Was Snowden a Soviet Agent?’ The Russian official media, in their turn, have been producing waves of anti-Western rhetoric for a few years now, but the Ukraine crisis and the sanctions put in place by the US, Canada and the EU sent them to fevered new heights.

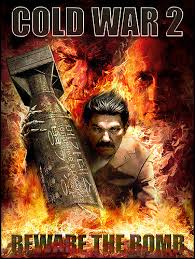

All this makes it hard to shake the feeling that we are living through a deranged re-run of the Cold War. Of course, the idea of a reprise of the superpower stand-off that dominated the 20th century has been in the air more or less since the actual Cold War ended, the stuff of countless think-tank briefings and film plots. But it has gained particular force over the last decade or so, supplying a ready-made framework for understanding the mounting tensions between Russia and the West – especially since the Russo-Georgian war of August 2008.

For one current of opinion, that conflict provided yet more evidence that Putin’s Russia had reverted to Soviet type, bent on dominating its neighbours just as the USSR and the Tsarist empire had been. From this perspective, Russia and the West are locked in the same old geopolitical struggle, an authoritarian power pitted against the world’s democracies.

A more even-handed version of the ‘new Cold War’ argument doesn’t see the recent downturn in US-Russian relations as a straight reversion to the familiar pattern, but holds instead that it is in various ways comparable to the polarisation that set in soon after 1945 – the Cold War standing in this case as both analogy and warning. In Return to Cold War, Robert Legvold – a specialist in post-Soviet foreign policy and regular contributor to Foreign Affairs – sees worrying similarities between the current situation and the early stages of the Cold War (c.1948-53), focusing in particular on the rhetorical framing of the conflict on each side, and on the seriousness of the potential outcomes.

Then as now, in his view, each side assumed the other alone was at fault – ‘the essence of the conflict was in the other side’s essence’ – while the zero-sum character of the confrontation also meant that both parties felt it ‘could end only with either a fundamental change in the other side or its collapse’. Moreover, the globally interlinked nature of the Cold War meant that ‘trouble in one area metastasized to others,’ and Legvold sees the current situation in similar terms: bitterness over Ukraine has choked off co-operation on a range of issues, most notably nuclear arms reduction and non-proliferation. The clash between Russia and the West, according to Legvold, threatens to ‘cripple efforts to come to grips with the 21st century’s new challenges’, from terrorism to climate change to cyber warfare.

Legvold may be right that the rhetoric coming from either side could have material effects. The notion of a ‘cold war’ is a kind of geopolitical speech act: if enough people in power decide they are in one, it will materialize. But there are decisive differences between the Cold War contest and current frictions between Russia and the West: the lack of remotely comparable ideological stakes; the greatly reduced number of players (this time around, China, East and South Asia, Africa and Latin America are all bystanders); and the much more geographically circumscribed nature of the struggle (with the grim exception of Syria, the zones of contention have been in Eastern Europe). In short, it makes more sense to say that both Russia and the world have been so transformed over the past generation that none of the Cold War conditions can be said to apply. In Should We Fear Russia? Dmitri Trenin (a career officer in the Soviet and then Russian army for twenty years, including stints in Iraq and East Germany; he now runs the Carnegie Endowment’s Moscow office) calmly and concisely sets out this line of argument. In his view, the current rivalry between Washington and its allies on one side and Russia on the other is ‘more fluid and less predictable’ than the 20th-century stand-off had been. But this in itself is cause for concern: his Tolstoyan verdict is that ‘the situation in Western-Russian relations may now be as bad, and as dangerous, as at any time during the Cold War, but it is bad and dangerous in its own new way…’