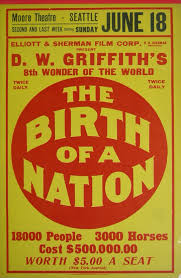

Birth of a Nation…Where Art and Racism Meet

Birth of a Nation…where art and racism meet…art can touch us deeply

It can inspire us, heal us and even change us, It can also speak to the

darkest corners of our beingD.W. Griffith, a Kentuckian born shortly after the American Civil War, was the son of a Confederate colonel. After several attempts at acting and play writing, he became a director in the early days of movie-making. Birth of a Nation, a film with which Griffith’s name became synonymous, was released in 1915 and caused riots in several American cities because of its racist message. The film is based on The Clansman, a novel whose message was so crudely racist that even the white supremacist Griffith felt constrained (for whatever reason) to try to tone it down a bit.

Birth of a Nation is purely and simply racist

To this day film students, film buffs and historians are amazed at how an offensive and false message – i.e. that Blacks are inferior to Whites – can be presented in a way that is still praised – exactly 100 years after the debut of the film -.for its technical virtuposity. Many of the techniques used by Griffith in the making of Birth of a Nation are noted for their originality, and taught in film schools all over the world.

Birth of a Nation…where art and racism meet

The following article was taken from Worldhistory.net. This article was written by Eric Niderost and originally published in the October 2005 issue of American History Magazine:

On July 4, 1914, director D.W. Griffith began on a new movie called The Clansman, an epic about the Civil War and the subsequent agonies of Reconstruction. It was a major production, an epic in every sense of the word, with sets that seemingly filled every foot of his Fine Arts Studio in Hollywood, California.

D.W. Griffith was a Victorian

Griffith was a curious figure who didn’t conform to the popular image of a silent-film director. Unlike his contemporary Cecil B. DeMille, he eschewed the usual costume of rolled-up sleeves, jodhpurs and riding boots, opting instead for a crisply tailored business suit complete with celluloid collar and immaculate tie. It was an outfit more in keeping with the boardroom than the cutting room, but it somehow reflected Griffith’s reserved Victorian persona.

Based on Thomas Dixon’s book The Clansman

The Clansman, later retitled The Birth of a Nation, is still considered a landmark of the American cinema. The film has been praised for its technical virtuosity and damned for its demeaning and racist depiction of black Americans. Birth was a kind of rite of passage for American movies, marking a transition from crude infancy to a robust adolescence. Griffith and his cameraman Billy Bitzer used a dazzling array of techniques to propel the story forward. Moving, tracking and panning shots gave new life to even static scenes. Crosscutting between two scenes built suspense, and the use of ‘cameo profiles and close-ups gave the movie a new emotional intimacy.

Although Griffith did not invent these techniques, he used them in such brilliant and innovative ways that it seemed as if he had. The director was a master storyteller, and by 1914 he was at the height of his powers. Monumental in conception, epic in scope and narrative power, the movie influenced filmmakers for generations to come. The Birth of a Nation was pure Griffith, and every frame of celluloid bore his stamp.

Griffith the son of a Confederate colonel

David Wark Griffith, son of Jacob Wark Griffith, was born on January 22, 1875, in Floydsfork, later Crestwood, Ky. The older man, nicknamed Roaring Jake, was a veteran Confederate colonel who had once commanded the 1st Kentucky Cavalry during the Civil War. Roaring Jake filled young David’s head with nostalgic tales of dashing, gray-clad cavaliers defending the antebellum way of life.

Slavery gave way to serfdom in the South

The Confederacy was no more, and slavery had been abolished, but by 1880 most of the civil rights that blacks had enjoyed immediately after the war had been taken away by newly reestablished white supremacist state governments. The Peculiar Institution, chattel slavery, had been replaced by a kind of serfdom in which black sharecroppers, debt-ridden and disenfranchised, were relegated to second-class citizenship.

Jacob Griffith died suddenly when David was only 10. The old colonel had been badly wounded in the war, and there was speculation that the injuries had been responsible — at least in part — for his demise. In any case, Roaring Jake’s passing caused quite a commotion, and his deathbed scene was forever etched in young David’s memory.

In later years, the director took great pains to hide his true self from the public, adopting a patrician reserve that exuded an air of mystery. But when he described his father’s death, he also unintentionally revealed his own deeply cherished core beliefs. When Griffith entered his father’s bedroom, he later recalled, he was met by a scene of grief and lamentation: Four old n_____were standing in the back at the foot of the bed weeping freely. I am quite sure they really loved him.

Griffith’s racism

The unconscious racism and implied unquestioning acceptance of black inferiority in that statement reflect Griffith’s view of black-white relations. Thirty years later, those attitudes would find new expression in The Birth of a Nation.